CVAM care bundles: how we can measure their economic benefit

Central vascular access devices (CVADs) allow for blood collection, nutritional support and medication administration when these cannot be provided safely through peripheral vascular access devices (PVADs)1.

However, intravenous (IV) therapy with CVADs are associated with frequent preventable complications, morbidity and healthcare costs1,2. Over 15% of patients who receive CVADs experience complications1.

More on this topic: What is the real cost of vascular access-related complications?

CVAM care bundles: assessment with a health economics model

A health economic model has been developed to estimate the number and cost of complications, the cost of consumables, and nurse time spent managing catheters for a cohort of patients, where the risk of complications could be varied by the length of catheter placement and the expected impact of the vascular access management (VAM) strategies selected.

This model compares two strategies including catheter selection and insertion and care and maintenance practices: one considered as a CVAM baseline/current practice and the other as a best practice BD CVAM care bundle.

The BD CVAM care bundle is an integrated approach for vascular access device selection, placement, and care designed to help reduce vascular access related complications which may lead to improved patient care.

The baseline practice utilised in the model includes: skin preparation with 5% povidone iodine and 69% ethanol, subcutaneous engineered stabilisation devices (SESDs), no needleless connectors, no disinfecting caps and intermittent flushing of the line.

The BD CVAM care bundle includes: skin preparation with single-use applicators containing 2% chlorhexidine gluconate in 70% isopropyl alcohol (CHG-IPA), peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) stablisation devices, positive-displacement needleless connectors, disinfecting caps and single-use pre-filled saline syringes.

The use of disinfecting caps and pre-filled saline syringes has been found to reduce the time needed for catheter maintenance3,4.

Zoom in on health economics

This health economics model helps predict the budget impact when moving from baseline practice to the BD CVAM care bundle:

- Pooling clinical evidence on best practice in CVAM and calculating risks of each complication type

- Calculating the cost of care and maintenance: catheter flushing, fixation, hub and skin disinfection

- Estimating the occurrence of complications and costs by type for peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) or acute central venous catheters (CVCs)

The model takes these factors into account:

- Dwell time of the catheter

- Catheter type: PICCs and acute CVCs

- Frequency of catheter maintenance

- Consumable costs

- Cost of these three complication types: infection, occlusion and dislodgement

More on this topic: How can we measure the economic benefit of a peripheral vascular access management care bundle?

The estimated impact of the CVAM care bundle

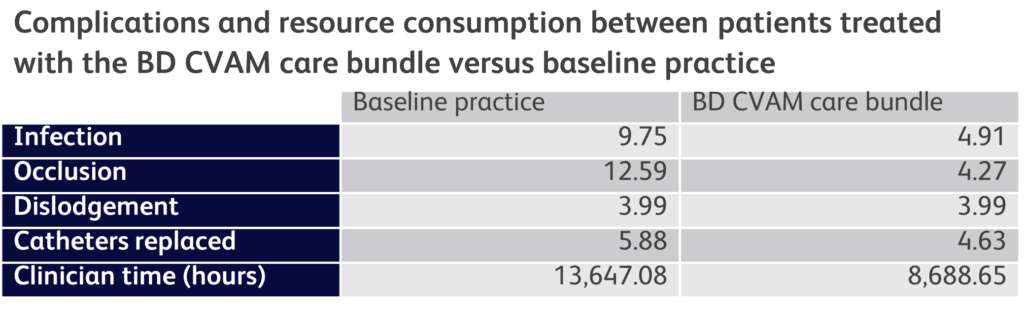

Based on a case scenario involving 1,000 patients inserted with PICCs for 15 days, the estimated impact of the BD CVAM care bundle is estimated to lead to 13 fewer complications including five catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs), as well as saving around 5,000 hours of clinicians’ time.

By applying the BD CVAM care bundle to 1,000 patients, an estimated €169,753 could be saved (including €143,613 for catheter maintenance practices, €26,139 for the cost of complications) when compared with the baseline practice used in the model2,5,6.

Using a CVAM health economics model to estimate the clinical and economic impact of the BD CVAM care bundle strategy can help implement best practice clinical procedures while reducing overall costs.

To find out how this model could be used to help estimate improvements in your CVAM practice, contact us below.

References

- McGee DC, Gould MK. Preventing complications of central venous catheterization. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(12):1123-1133. doi:10.1056/NEJMra011883

- Baskin JL, Reiss U, Wilimas JA, et al. Thrombolytic therapy for central venous catheter occlusion. Haematologica. 2012;97(5):641-650. doi:10.3324/haematol.2011.050492

- Cameron-Watson C. Port protectors in clinical practice: an audit. Br J Nurs. 2016;25(8):S25-31. doi:10.12968/bjon.2016.25.8.S25

- Keogh S, Marsh N, Higgins N, Davies K, Rickard C. A time and motion study of peripheral venous catheter flushing practice using manually prepared and prefilled flush syringes. J Infus Nurs. 2014;37(2):96-101. doi:10.1097/NAN.0000000000000024

- Walker G, Todd A. Nurse-led PICC insertion: is it cost effective? Br J Nurs. 2013;22(19):S9-15. doi:10.12968/bjon.2013.22.Sup19.S9

- Cooper K, Frampton G, Harris P, et al. Are educational interventions to prevent catheter-related bloodstream infections in intensive care unit cost-effective? J Hosp Infect. 2014;86(1):47-52. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2013.09.004

This list of references to third-party peer-reviewed material and the sites they are hosted on are provided for your reference and convenience only, and do not imply any review or endorsement of the material or any association with their operators. The Third-Party References (and the Web sites to which they link) may contain information that is inaccurate, incomplete, or outdated. Your access and use of the Third Party Sites (and any Web sites to which they link) is solely at your own risk.

BD-78066