“Complications of IV catheter therapy are simply the result of one complex and highly variable mechanical system—IV catheter equipment design, placement, use and care—being applied to a second complex and highly variable system—the ailing human body.”1

— Dr. Robert E. Helm

A complication is defined as an observable event that disrupts the intravenous (IV) catheter, interupts delivery of IV solution or physically harms the patient.2 These complications can be mechanical or infectious.2

IV complications can interrupt and delay treatment for underlying medical disorders and affect patient outcomes.3 They may increase morbidity and mortality.3 They also impact healthcare professionals because the time they spend managing complications could be saved to focus on better patient care.

Catheter-related bloodstream infection

10–20% of healthcare-associated infections in the United Kingdom are due to catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI)1

What is catheter-related bloodstream infection?

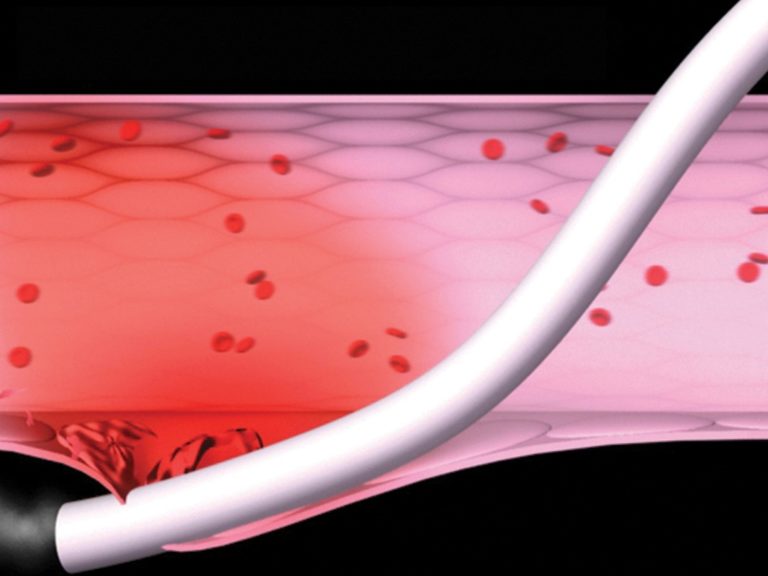

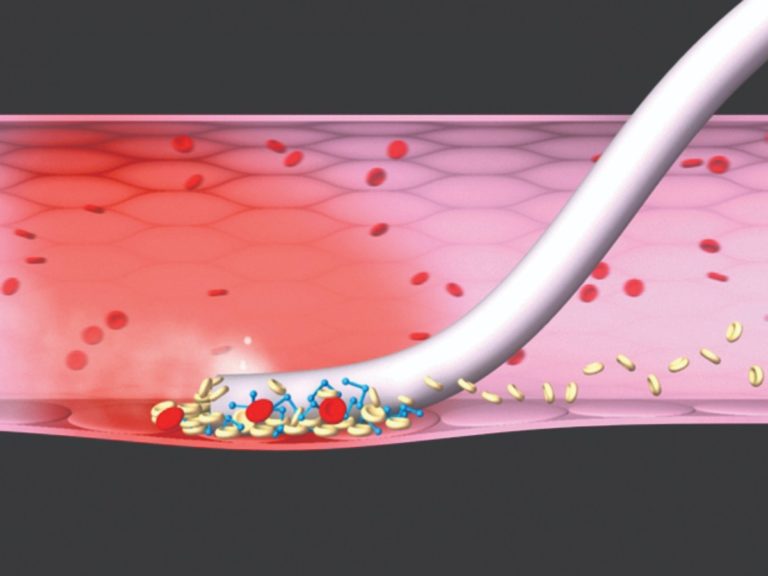

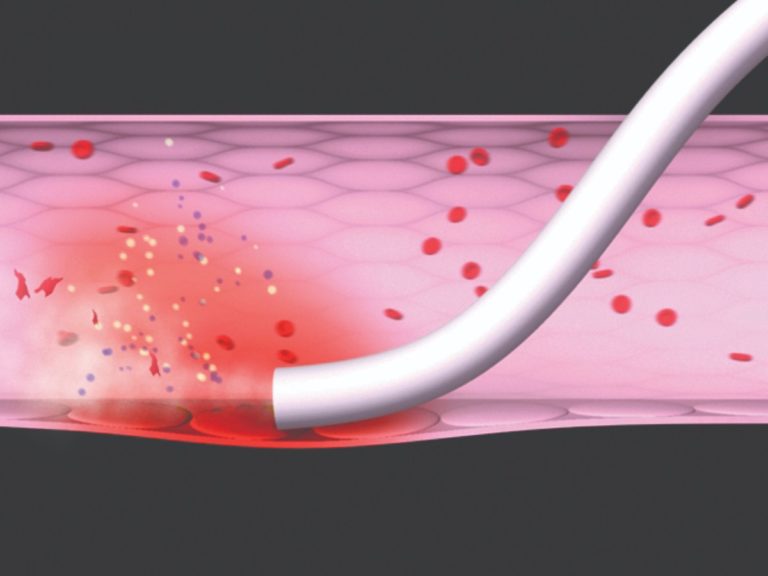

CRBSI occurs when a positive culture confirms the presence of bacteremia originating from an intravenous (IV) catheter.1,2 IV catheter colonisation can appear on extraluminal or intraluminal surfaces.2 CRBSI can result from inadequate skin preparation, a break in aseptic technique during vascular access placement or dressing, colonisation of the catheter tip from skin flora and cutaneous tract or inadequate catheter care and maintenance procedures.1,2

Central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) occurs within 48 hours of central venous catheter (CVC) placement without being related to infection at another site.3 CLABSI is one of the most widespread, deadly and expensive complications of CVC placement.1

Catheter-associated bloodstream infection (CABSI) refers to bloodstream infections (BSIs) originating from either peripheral intravenous catheters (PIVCs) and/or central vascular access devices (CVADs).4 Now that you know what CRBSI and CLABSI are, let’s look at the signs and symptoms of these types of infections.

What are the signs and symptoms of catheter-related bloodstream infection?

The following signs and symptoms may indicate a catheter-related infection:1

- Malaise

- Nausea

- Chills

- High fever with rigours

- Vomiting

- Unexplained hypotension

These symptoms may indicate an exit-site infection:1

- Erythema

- Swelling

- Tenderness

- Purulent drainage

Now that you know the signs and symptoms, let’s look at how you can help prevent infections associated with IV catheters.

Ten ways to help prevent catheter-related bloodstream infection

- Choose appropriate vascular access device based on intended purpose, duration, patient characteristics, medication characteristics and experience of catheter operator.5

- Utilise maximum sterile barrier precautions.5

- Carry out skin antisepsis at the infection site before insertion and during routine care.4

- Insert catheters as far from open wounds as possible.5

- Avoid placing CVCs in the femoral vein in adult patients.5

- Place nontunneled CVCs at a subclavian site, rather than a jugular or femoral site in adult patients.5

- Use ultrasound guidance to place CVCs.5

- Implement a care bundle with a culture of safety.4

- Daily assess the insertion site.5

- Remove any catheter that is no longer being used.5

References

- Gahlot R, Nigam C, Kumar V, Yadav G, Anupurba S. Catheter-related bloodstream infections. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2014;4(2):162-167. doi:10.4103/2229-5151.134184

- Helm RE, Klausner JD, Klemperer JD, Flint LM, Huang E. Accepted but unacceptable: peripheral IV catheter failure. J Infus Nurs. 2015;38(3):189-203. doi:10.1097/NAN.0000000000000100

- The Joint Commission. Preventing Central Line–Associated Bloodstream Infections A Global Challenge, A Global Perspective. Joint Commission Resources; 2012.

- Gorski LA, Hadaway L, Hagle ME, et al. Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice, 8th Edition. J Infus Nurs. 2021;44(1S Suppl 1):S1-S224. doi:10.1097/NAN.0000000000000396

- O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. Guidelines for the Prevention of Intravascular Catheter-related Infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(9):e162-93. doi:10.1093/cid/cir257

This list of references to third-party peer-reviewed material and the sites they are hosted on are provided for your reference and convenience only, and do not imply any review or endorsement of the material or any association with their operators. The Third-Party References (and the Web sites to which they link) may contain information that is inaccurate, incomplete, or outdated. Your access and use of the Third Party Sites (and any Web sites to which they link) is solely at your own risk.

References

- Helm RE, Klausner JD, Klemperer JD, Flint LM, Huang E. Accepted but unacceptable: peripheral IV catheter failure. J Infus Nurs. 2015;38(3):189-203. doi:10.1097/NAN.0000000000000100

- Marsigliese A. Evaluation of Comfort Levels and Complication Rates as Determined by Peripheral Intravenous Catheter Sites. University of Windsor; 2000. Accessed March 22, 2023. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2977&context=etd

- Baskin JL, Pui CH, Reiss U, et al. Management of occlusion and thrombosis associated with long-term indwelling central venous catheters. Lancet. 2009;374(9684):159-169. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60220-8

This list of references to third-party peer-reviewed material and the sites they are hosted on are provided for your reference and convenience only, and do not imply any review or endorsement of the material or any association with their operators. The Third-Party References (and the Web sites to which they link) may contain information that is inaccurate, incomplete, or outdated. Your access and use of the Third Party Sites (and any Web sites to which they link) is solely at your own risk.