Reliable triage methods are key in HPV primary cervical cancer screening

Extended genotyping in combination with liquid-based cytology take cervical cancer screening triage to the next level.1-4

In the HPV primary screening approach, when the HPV test result is positive, a triage test can be performed in order to inform the appropriate patient management strategy. The result of the triage test helps determine whether the patient needs a colposcopy with biopsy, a treatment or a simple follow-up evaluation at a specified timeframe.5

There are multiple triage strategies possible after a positive HPV test, including HPV genotyping, cytology testing, visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) or colposcopy.5

By choosing a reliable triage test after an initial HPV primary positive result, clinicians can better identify women* with precancerous lesions and women at high risk of cervical disease. Another benefit of precise triage is to reduce the need for unnecessary colposcopies and treatment for those women who are at lower risk.1-4

HPV genotyping – and more so, extended genotyping – provides information on the immediate and future risk of cervical precancer of people with a cervix and can be integrated into the initial HPV test.1,2,5

Liquid-based cytology uses a standardised sample collection that significantly enhances specimen quality and detection of cervical lesions.3,4 In addition, it can be performed on the same sample as the initial HPV test.

Extended genotyping is advancing HPV testing and enhancing clinical management by providing specific, actionable insights to assist in reducing patient call-backs and unnecessary colposcopies.1

There are 12 high-risk HPV genotypes identified as oncogenic:

HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59.6

Yet, HPV genotypes vary in prevalence, but also in their potential to cause cervical lesions.1,2,6

HPV 16 and 18 are responsible for about 74% of all cervical cancer cases in Europe and have been targeted by vaccination since 2006.6,7

But not all HPV tests are equivalent. By identifying which HPV genotype is present, HPV extended genotyping can stratify the risk of CIN3+ to help guide clinical decision.1,8 In this aspect, cytology and partial genotyping provide restrained information for the evaluation of true clinical risk.8

PARTIAL GENOTYPING

HPV tests with partial genotyping report multiple HPV genotypes in a single result,1 which may:

- Mask the true risk of pre-cancer due to HPV 31, 33, 45, 52 or 582

- Prohibit monitoring of genotype-specific HPV persistence beyond HPV 16 and 182

EXTENDED GENOTYPING

HPV tests with extended genotyping report at least 6 HPV genotypes individually,1 which is important to:

- Provide relevant information and eliminate the need to run additional tests thanks to the identification of 31, 33, 45, 52 or 581,2

- Track genotype-specific HPV persistence,2 the most important determinant of cervical cancer risk in people with a cervix who test HPV positive9,10

FULL GENOTYPING

HPV tests with full genotyping report every single hrHPV genotype individually.1

The concept of grouping HPV genotypes into clusters may ease the implementation of HPV testing information into screening algorithms as it simplifies the clinical management.1,8,11

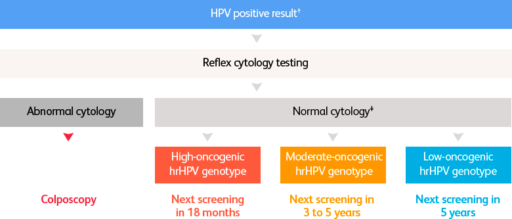

What differentiated patient management could look like in the future*12

Currently, only one HPV test provides extended genotyping and is CE-marked and FDA-approved for HPV primary screening.13,14

BD Onclarity™ HPV Assay: Results

you can trust

Liquid-based cytology has revolutionised Pap screening by significantly enhancing specimen quality and detection of cervical lesions and reducing patient call-backs while improving cost-effectiveness.3,4

Cervical cancer incidence and mortality has declined by 70% since the introduction of Pap screening in developed countries with well-established screening programmes, and in which people with a cervix are screened at regular intervals.15

However, not all Pap tests are the same. Conventional Pap testing comes with many limitations that may lead to inaccuracies and equivocal diagnoses.16

Comparison of conventional and liquid-based cytology.3,4

| Principle |

Conventional Pap test Brush contents are smeared directly onto the slide

|

Liquid-based cytology (LBC)

|

| Standardised sample collection | Variability in sample collection |

|

| Slide preparation | Manual | Automated |

| Little to no obscuring material | ||

| Easy slide evaluation | ||

| Reduced screening time | ||

| Performance | Frequent unsatisfactory reports |

|

| Additional testing | Not always possible |

|

The BD SurePath™ Liquid-based Pap Test outperforms conventional and other liquid-based cytology methods.4,17,18

BD Surepath™ Liquid-based Pap

Test

* Hypothetical patient management algorithm, adapted from the proposed new screening algorithm for the national cervical cancer prevention programme in Sweden.12

† Depending on age and other factors, some low-oncogenic hrHPV genotypes might not require cytology testing.12

‡ Depending on age and other clinical parameters.12

ASC-US, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; CIN3+, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or higher; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; hr, high-risk; HPV, human papillomavirus; LBC, liquid-based cytology; Pap, Papanicolaou.

1. Bonde JH et al. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020;24(1):1–13.

2. Stoler MH et al. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;153(1):26–33.

3. Hoda RS et al. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41(3):257–78.

4. Rozemeijer K et al. BMJ. 2017;356:j504.

5. World Health Organization. WHO Guideline for Screening and Treatment of Cervical Pre-Cancer Lesions for Cervical Cancer Prevention – Second Edition. 2021.

6. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in Europe. Summary Report. 2021.

7. European Medicines Agency. Gardasil Product information. 2022.

8. Gilham C et al. Health Technol Assess. 2019;23(28):1-44.

9. Bodily J and Laimins LA. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19(1):33–9.

10. Elfgren K et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(3):264.e1–7.

11. Demarco M et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;22:100293.

12. Regionala cancercentrum i samverkan. Cervixcancerprevention. Nationellt vårdprogram. Remissversion. Version: 4.0. Last updated 19 Apr 2022. Accessed 10 Oct 2022. Available at:

https://cancercentrum.se/globalassets/vara-uppdrag/kunskapsstyrning/vardprogram/kommande-vardprogram/2022/220419/nationellt-vardprogram-livmoderhalscancerprevention-remissversion.pdf.

13. Arbyn M et al. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(8):1083–95.

14. Salazar KL et al. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2019;8(5):284–92.

15. Bedell SL et al. Sex Med Rev. 2020;8(1):28–37.

16. Gibb RK and Martens MG. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011;4(Suppl 1):S2–S11.

17. Fremont-Smith M et al. Cancer. 2004;102(5):269–79.

18. Nance KV. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35(3):148–53.